The Suffering Servants

The Suffering Servant is the only role model who can dissuade people from trying to claw their way to the top, ignorant of those they step on.

The Suffering Servants

2024-56

sermon preached at Church of the Good Shepherd, Federal Way, WA

www.goodshepherdfw.org

by the Rev. Josh Hosler, Rector

Twenty-Second Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 24B), October 20, 2024

Isaiah 53:4-12 ;

Psalm 91:9-16 ;

Hebrews 5:1-10 ;

Mark 10:35-45

One of my favorite movies purportedly for children is called Nausicäa of the Valley of the Wind. It’s an animated film made forty years ago by Hayao Miyazaki, and it’s about a teenage girl growing up in the midst of a slow-moving environmental crisis. In other words, it’s deeply prophetic.

Early in the movie, Nausicäa’s village is attacked by a local strongman who assassinates her ailing father, the king, while he lies in bed. Witnessing this, Nausicäa flies into a rage and attacks the enemy soldiers. Suddenly her mentor, Master Yupa, steps right into the middle of the violence, and Nausicäa finds that she has driven her sword deep into Yupa’s arm. Yupa stands there, unyielding, as the blood runs down. For that day, all the violence stops.

Later in the film, in a moment when others around her are panicked, Nausicäa removes her gas mask and breathes polluted air to get everyone to stop panicking. And by the end of the film, she puts her very life on the line to stop rage and violence in its tracks.

Everyone experiences pain and suffering, but not everybody chooses it readily. What is the nature of pain and suffering? Why must we go through it? And under what conditions might we take it on for others?

In his 1943 book The Problem of Pain, C. S. Lewis wrote that pain is God’s “megaphone to rouse a deaf world.” If God didn’t use pain to get our attention, wrote Lewis, we would have no idea how much we need God or what God wants of us.

Eighteen years later, Lewis’s wife Joy died of cancer. And though I can’t find the quote, I’m sure I remember that he remarked,

“I wish I’d known more about pain when I wrote The Problem of Pain.”

The odd thing about pain, of course, is that it looks different to the outsider than to the insider. We can talk and theorize about pain logically: “Well, if we had no pain receptors, we’d never know anything was wrong. If we didn’t hurt for others, we wouldn’t be motivated to act compassionately. If we didn’t miss people who had died, it would only reveal that their lives didn’t matter to begin with.” All of this makes sense, of course. But would you say any of this to someone who is actually in pain? I wouldn’t. No matter your suffering, you can be certain that I haven’t suffered in the same way you have.

So what is the meaning of suffering? Or is it possible that our suffering is meaningless? In our first reading today, we heard the Prophet Isaiah speak about a poetic biblical figure commonly called the Suffering Servant:

Surely he has borne our infirmities

and carried our diseases;

yet we accounted him stricken,

struck down by God, and afflicted.

But he was wounded for our transgressions,

crushed for our iniquities;

upon him was the punishment that made us whole,

and by his bruises we are healed.

It’s no wonder that the first Christians looked at Isaiah’s writing and said, “A-ha! That’s Jesus he’s talking about.” Way back in the Acts of the Apostles, when Philip encounters a eunuch from Ethiopia, this is the passage of scripture they discuss, and Philip uses it to point precisely to Jesus of Nazareth. And so, with this passage always in the background, various theologies began to form about the purpose and meaning of Christ’s suffering, death, and resurrection. It became commonplace among Christians to assume that Isaiah was predicting the coming of Jesus some 700 years later.

But let’s not begin with that assumption. Let’s wonder for ourselves: “Who is the Suffering Servant?”

Let’s ask James and John, who in today’s Gospel want to be Jesus’ right- and left-hand men. All they can think about is grabbing power, but Jesus retorts: “You don’t know what you are asking. Are you able to drink the cup that I drink?”

The silly fools answer: “Yes! We’re your men.”

“OK then,” says Jesus, “you will drink that cup.” (At this point, a shiver is in order, because we hear about that cup every year on Good Friday. A decade after that, King Herod Agrippa I ordered the murder of James, and although nobody knows for sure, some traditions hold that John, too, died a violent death.) Jesus tells them, “Your image of sitting at my right and left hand is completely the wrong image. If you really think this is a contest, then you’d better stop racing to the top and start racing to the bottom. You’d better become Suffering Servants.”

In other words, it’s useless to play the game of who loves Jesus more, or to do good deeds expecting a reward. It’s useless to try to be good so you can get into heaven. These intentions are misplaced and shortsighted. Doing God’s work in the world is a labor of love, and when we love others, we are willing to suffer for them—to take up a cross on their behalf. Jesus knew that Isaiah spoke the truth: the Suffering Servant is the only role model who can dissuade people from trying to claw their way to the top, ignorant of those they step on. The Suffering Servant transforms the entire situation.

The author of the letter to the Hebrews also has servanthood in mind when he refers to Melchizedek. Who was Melchizedek, anyway? Well, he was a minor character early in the Book of Genesis. Melchizedek was the king of the proto-community of Jerusalem—in fact, his name means “righteous king”—yet he brought Abram bread and wine and blessed him after a hard battle. In gratitude, Abram gave Melchizedek one tenth—a tithe—of all he had. (Take note, potential pledgers—bread and wine! One tenth! Dynamic relationship!) Melchizedek is immortalized in one of the Psalms, and later in this letter to the Hebrews. He is held up as a model for priesthood, a model to which the author compares Jesus, our “great high priest.”

I think Isaiah may also have had Melchizedek in mind, but he took that servanthood idea further—not just humble, mutual stewardship, but also suffering. And then Jesus, reflecting on both Melchizedek and Isaiah, went even further, embracing death instead of power—even constructive power. Jesus could have been a political revolutionary and accomplished wonderful things for his own people, but instead, he took on a much more powerful, long-term work for the entire world, a labor of love that walked him right into the middle of suffering for the sake of those enduring it.

In other words, it’s not the violence against the Suffering Servant that redeems us. Violence can never redeem anything. But to bear the brunt of the violence you cannot prevent—and not strike back? Like Nausicäa’s mentor Yupa?

So who is the Suffering Servant? It may seem that we’ve established him to be Jesus. That is the standard Christian answer, and I won’t tell you it’s wrong. But what good it would do for Isaiah to predict the coming of a suffering savior so many centuries in the future? Isn’t that a little like telling a grieving person, “It’ll all be OK”? In the same way, I won’t just stand here and tell you, “The Suffering Servant was Jesus 2000 years ago,” and leave it at that.

Instead, I want to suggest that the Suffering Servant is Anne, a girl who wrote in her diary that she loved God and humanity with her whole heart … and then she died in a concentration camp.

The Suffering Servant is Matthew, a young acolyte in his Episcopal Church in Wyoming. He was lynched because he was gay, but he inspired many in our country to change their hearts, and 20 years after his death, he was interred in the National Cathedral.

The Suffering Servant is Malala, a teenage Pakistani blogger who was shot in the head by the Taliban because her hunger for learning was a threat to their evil ideology. Yet she survived, and as an adult, she continues to work on behalf of girls who simply want an education.

The Suffering Servant is Nancy, a woman from Louisiana who learned the 10-week-old fetus she was carrying could never survive outside her womb … yet she had to travel to a different state to find a doctor who would protect her health and relieve her grief.

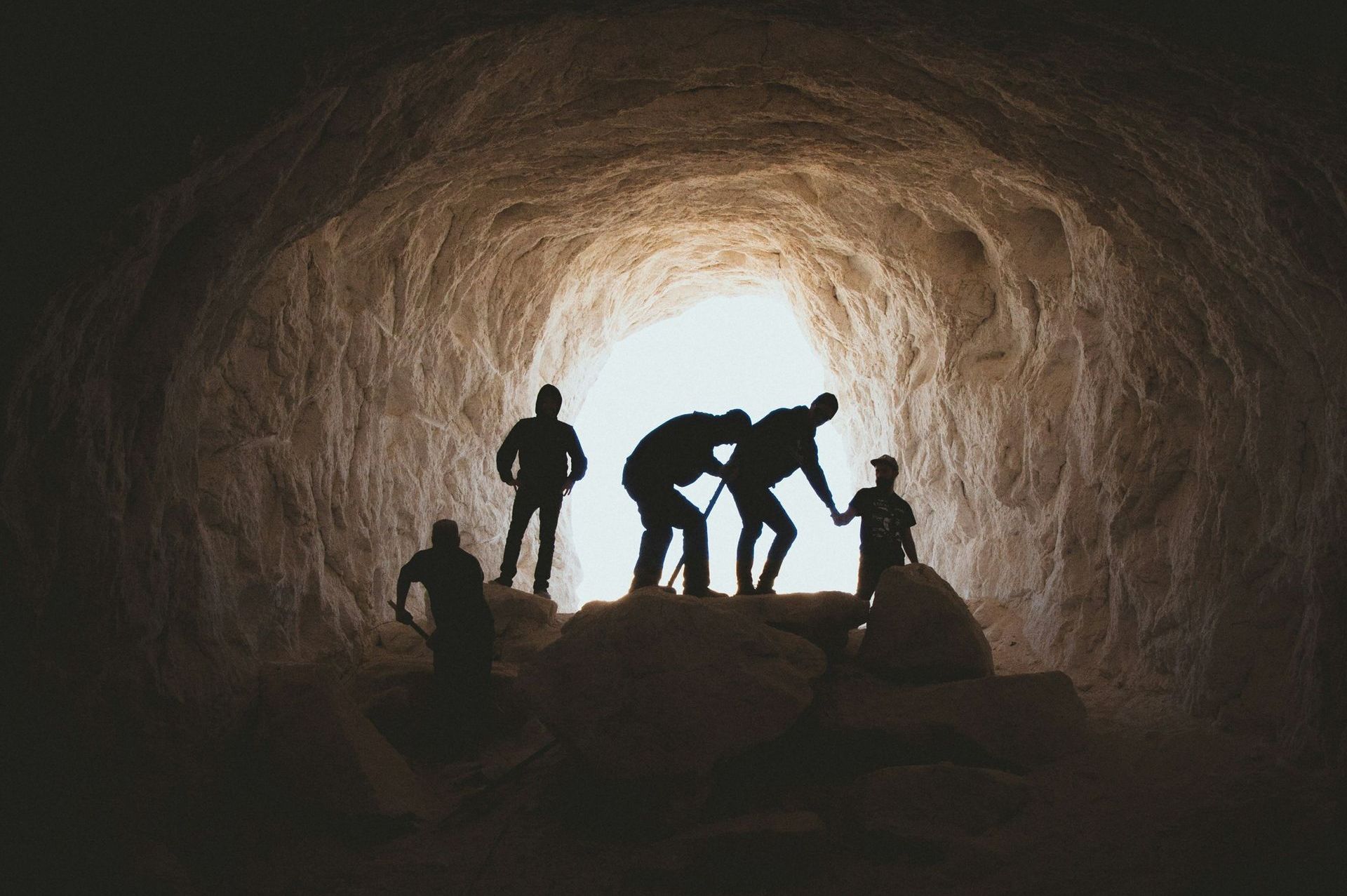

The Suffering Servant is a young Baptist pastor marching for freedom, and an unlikely Salvadoran archbishop preaching liberation. The Suffering Servant is a Palestinian child starving in Gaza and a Congolese child grieving the deaths of her parents. Elders in failing health and their caregivers are Suffering Servants, and the children of Uvalde, and the flooded in

Asheville, and the downsized and indebted and disenfranchised.

And yes, the Suffering Servant is a man who urged us to love one another, who healed us and blessed us and fed us, and whom the Roman Empire executed as a criminal. These are the suffering servants of God. These are the people who have become prophets by the experiences that they endured, wittingly or unwittingly, and by their obedience to the call of love. So if you really must imagine seats to the right and left of Jesus, then these Suffering Servants are the people you must place in them.

Have you been a Suffering Servant, enduring trial after trial and wondering when things might finally get better? It would be hypocritical of me to pat you on the shoulder and say, “There, there … I know how you feel.” I don’t know how you feel, because I’m not you.

But our faith tells us that Jesus is an insider. Because Jesus suffered, our Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer does know how we feel. In coming close to us, closer even than we are to ourselves, God chooses to take on our pain and suffering. This is the claim that makes us Christians. Jesus doesn’t die as a due punishment, a transaction required by an angry bloodthirsty deity. Jesus dies because he loves us with all the love that defines who God is.

If this is true—if God is truly with us in our suffering—then can any suffering be meaningless? I don’t know. I pray not. I pray that every sharp twinge, every burrowing ache, every hollow pit of despair is carved out of God, the God who is infinite and eternal and therefore cannot be depleted. When we can’t go on, I pray that God can, and that God will raise us up from our suffering and reveal to us a world so shot through with joy that we cannot yet imagine it.

Amen.