The Compassionate Shepherd

To be accountable to God means being accountable to compassion.

2024-43

sermon preached at Church of the Good Shepherd, Federal Way, WA

www.goodshepherdfw.org

by the Rev. Josh Hosler, Rector

Ninth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 11B), July 21, 2024

Jeremiah 23:1-6 ;

Psalm 23 ;

Ephesians 2:11-22 ;

Mark 6:30-34, 53-56

I tell a lot of stories about my time in Bellingham doing campus ministry. I have another brief one for you today. Our group was talking about how we wanted to spend our two-hour Sunday night meetings that semester. One student commented, “I want to know the Bible better. I know we read it in church every week. But it’s only in little snippets, and we don’t get the larger context. Can we just read the whole Bible together?”

I pointed out that the Bible is far too big to read in its entirety; most Christians never do. But we could pick one book of the Bible to read together straight through. They liked that idea, so I suggested the Gospel of Mark. As one of the four gospels, it’s super important for Christians to read it. And it’s so short that we could read it out loud within a single two-hour meeting.

I recommend that you do the same, and not by yourself. We hear from Mark’s gospel today, but we actually hear two snippets, with a snippet missing from the middle, sewn together for the lectionary with some amount of awkwardness. Notice the citation: it’s skipping some verses, but if we read all of them, it would be too long. Two events happen in the middle of today’s passage: the Feeding of the Five Thousand, and Jesus walking on the water to rejoin the disciples in their boat.

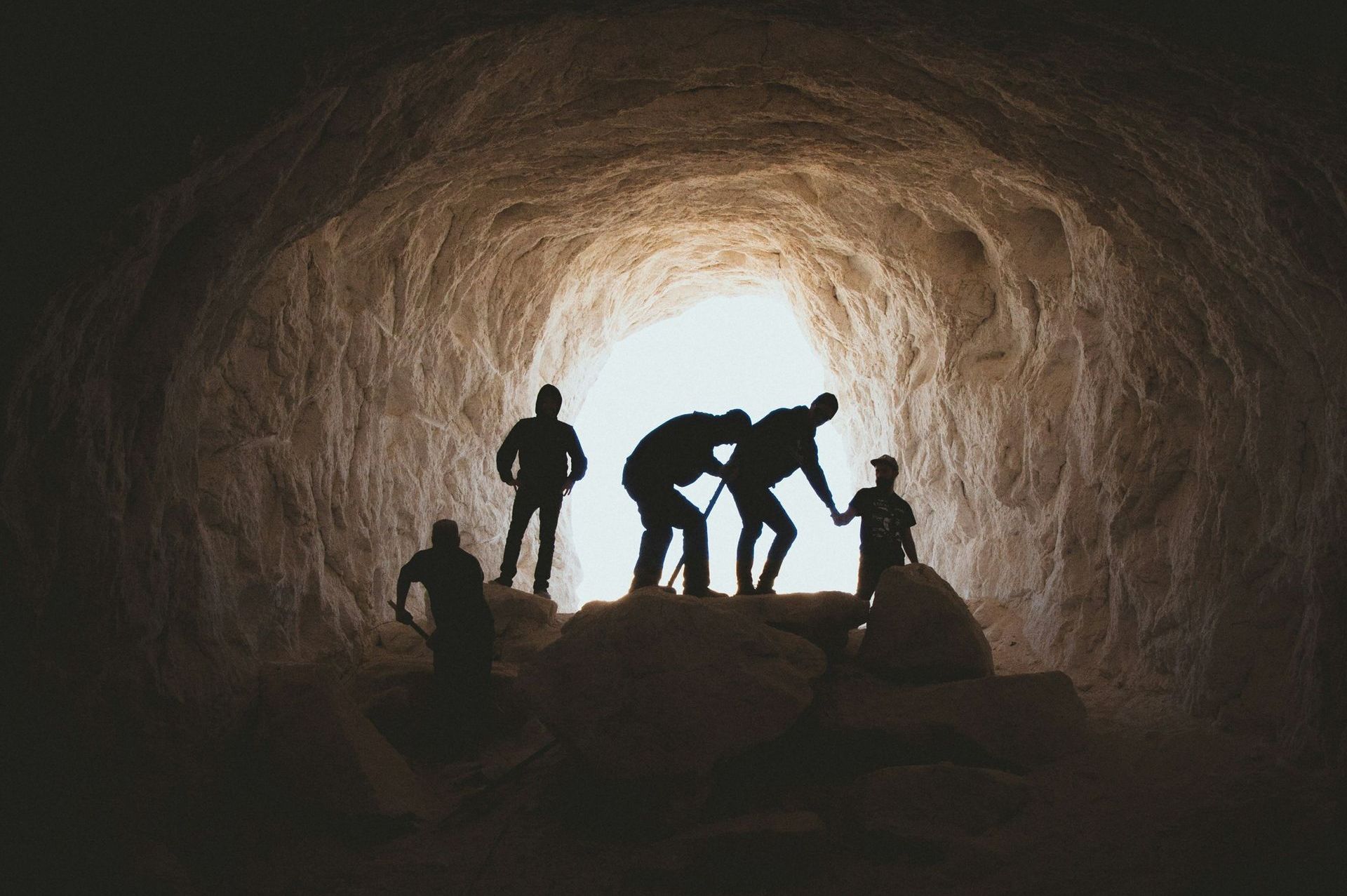

What happens before this passage? Jesus has sent the disciples out in twos to do exactly what he has been doing: to teach and to heal. The disciples are shocked to find that it’s not just Jesus; the power of God lies within them, too! But Jesus sees that they’re tired, so he offers them time away to rest.

Well, this plan doesn’t work out. When they arrive at the supposedly deserted place, thousands of people are there. Looks like someone tipped off the social media influencers and the paparazzi! But these aren’t just stans; they are people in need of healing words. We hear that Jesus “had compassion for them, because they were like sheep without a shepherd.”

Now, people who are “like sheep without a shepherd” have a tendency to grab onto the first shepherd who speaks as if he understands them and all their problems. Such shepherds don’t have to be honest—just charismatic. They don’t have to be compassionate, either—they just need to exude certainty. We see clearly that people who feel lost will eat that stuff up.

But more about sheep and shepherds in a bit. Jesus “had compassion for them,” so let’s try to suss out this word “compassion.” “Com” is a prefix meaning “with.” What does passion mean? Passion is a burning desire, right? But when something burns, it actually hurts. The meaning of the English word “passion” has changed over the years. When we reach back into Latin, we find that it simply means “suffering.” So, com plus passion: “suffering with.”

Jesus knows the disciples need rest. But he is also modeling for them a way of being that is intimately involved with the lives of others. We don’t just get to marshal our energy and distribute it in a logical way every day as we see fit. Sometimes the situation demands more of us. So Jesus begins teaching the crowd, and then he feeds them, somehow, with only five loaves of bread and two fish.

Huh, will you look at that? Sometimes we don’t think we have the resources we’ll need to give just a little bit more where it’s needed. Jesus shows us that it doesn’t take much. Indeed, just being willing to enter a situation with true compassion may provide the main source of fuel … and nourishment.

Surely you’ve been in this situation. It’s been a long day, you’re exhausted and maybe even a little discouraged. Then you come home and find out that someone still needs your energy: a spouse, a child, a friend. To have compassion is to say to yourself, “Well, I guess I’m not done yet today,” then take a deep breath and keep going. You are willing to suffer some measure of inconvenience or even discomfort and exhaustion … because somebody else needs you. So you jump into it with them, because sometimes our mere presence provides much of what the other person needs.

Now, it’s also true that when we’re tired, it’s harder to show compassion. In recent years we’ve learned a lot about “compassion fatigue,” which is actually a form of trauma marked by a large variety of symptoms. Without sufficient rest from the demands of compassion, we might find ourselves more scattered and unfocused, irritable and angry, or even in greater physical pain. Well, what do we expect? It’s called “suffering with.” But compassion fatigue also leads to a reduced ability even to feel compassion: our bodies begin blocking it as a form of self-protection and might even lead us to find ways to numb ourselves further. So we can’t just give and give and give. We do need to set up boundaries.

Did Jesus ever suffer from compassion fatigue? Yes. I look ahead in Mark’s gospel to chapter 9, where Jesus experiences the Transfiguration on the mountaintop, but when he comes back down the mountain, the disciples are frustrated because they are unable to perform a certain healing. This sets off Jesus’ frustration, too. He cries out, “You faithless generation, how much longer must I be among you? How much longer must I put up with you?”

Yes, Jesus, a human being, also got stressed out and blew his top.

What are the limits of your compassion? Can you tell when you’re beginning to wear out? What do you notice about yourself? A little self-awareness can prevent a lot of pain. I’ve learned a lot about my own reactions to stress—and even about compassion fatigue—since 2020!

How do you make sure you get enough rest? And how do you do so without neglecting the people who count on you? Have you made your boundaries clear to them? I bet most of us have not given this adequate thought. Either we’re more likely to withhold our energy because we fear we’ll run out, or we’re more likely to give and give and give until we burn ourselves out. It’s hard to find balance without real intention.

As Jesus modeled compassion, he also modeled shepherding. We heard from Jeremiah God’s complaints about the religious leaders of that time: “Woe to the shepherds who destroy and scatter the sheep of my pasture!” When God promises to appoint new shepherds, that’s not just to try to recover most of the sheep who have been scattered. We hear, “Nor shall any be missing.” Unlike some leaders—those who let themselves off the hook with the notion of “acceptable losses”—God never loses anyone.

This is the level of accountability to which God calls Israel to repent, and it’s the level of accountability to which Jesus calls his disciples: the kind that treats nobody as an enemy, and that drives out fear and despair. To be accountable to God means being accountable to compassion, and that means being accountable to all other people.

This work of Christ is summarized well in our passage today from the Letter to the Ephesians, which insists that Jews and non-Jews need no longer to be in opposition: “For he is our peace; in his flesh he has made both groups into one and has broken down the dividing wall, that is, the hostility between us … that he might … reconcile both groups to God in one body through the cross, thus putting to death that hostility through it.” Jesus puts an end to human hostility by serving as a shock to the system—a wake-up call to return to the ways of compassion.

The Christian claim is that Jesus has made all of us one, no matter what. Now, what will we do about that? Our track record over the past 2000 years hasn’t been great. But every day, we all get to wake up and decide how we will approach the other people in our world. To engage with our enemies as a Christian is to be clear that, ultimately, there is a spiritual reality in which we are no longer enemies. Every one of our interactions, even when we must actively oppose people’s evil efforts, needs never to lose sight of the reality Jesus has ushered in.

So when you commit to following Jesus, you commit to the Holy Spirit being your fuel, specifically as mediated through a community of fellow Christians. You don’t get to go it alone. We are always testing one another’s boundaries and stretching one another’s compassion. That’s the point. It’s a dynamic relationship that simply cannot happen in a vacuum. And the cornerstone of this structure is the one whose compassion was so great that he allowed his life to be taken from him. Because he refused to consider anybody his enemy.

Well, did the disciples ever get the rest Jesus offered them? Not that day. There were too many people in need of compassion. Skip ahead a bit in Mark’s gospel and you’ll find Jesus feeding another group of thousands, only to have to endure his disciples complaining in the boat later on because they have no bread. I can imagine Jesus smacking his head on the side of the boat. Have they learned nothing?

But how well have we learned? For all the times when our source of compassion came through for us, do we still withhold our compassion? And for all the times when we failed to account for our own need for rest, do we still overextend ourselves?

That might make for a good conversation after the service. All Christians are called to become compassionate shepherds. Tell stories of the times you withheld your energy and times when you gave it away too freely. What practices do you use to seek that balance—to re-ground yourself in the source of compassion that never runs dry?