Lifestyles of the Poor and Semi-Educated

Friends, our work as citizens and as Christians now continues

sermon preached at Church of the Good Shepherd, Federal Way, WA

www.goodshepherdfw.org

by the Rev. Josh Hosler, Rector

Twenty-Fifth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 27B), November 10, 2024

1 Kings 17:8-16 ;

Psalm 146 ;

Hebrews 9:24-28 ;

Mark 12:38-44

In the early 1990s, I was a music major at a small liberal arts school in Michigan. One the big attractions of Olivet College was that it had a radio station where I did my work study: I hosted the morning show three days a week. My friend Dave also worked at WOCR, and together, he and I did a weekly comedy bit. I played myself—my air name was “Da Sooper Yooper.” (You’ll understand that if you’ve ever lived in Michigan.) And Dave played none other than … Robin Leach, the Englishman who hosted the ’80s TV show Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

In our imagining, Robin Leach was now a washed-up former TV star who had squandered all his earnings and was desperate for gigs. So once a week he would sail across the Atlantic on a raft called the Splintery Sue, hitchhike to Southern Michigan, and appear on my morning radio show. I paid him in breadsticks from Tim’s Pizza, but I threatened to dock his pay every time he said something clueless—which was, of course, the source of the laughs.

The name of our show was Lifestyles of the Poor and Semi-Educated. Poor because, well, we were college students, and semi-educated because we hadn’t yet graduated. I still have recordings of some of our bits. Did Dave do a good impression of Robin Leach? No, not remotely! Were we funny? Maybe sometimes. I tell you what, though—we certainly cracked ourselves up. And in college radio, that’s what matters most.

I tell you this story partly because it’s quirky and personal and has nothing to do with the election. In fact, I wrote this entire sermon before the election and didn’t change it. This was advice from Bishop Phil, and I took it to heart.

But back to Lifestyles of the Poor and Semi-Educated. Could that be the title not only of an early ’90s small-town college radio feature, but also of a sermon? Why, yes. This week, yes, it could!

In the gospels, the spectrum of wealth and poverty is one of Jesus’ main concerns. Jesus understood that we humans are fascinated with money: who has it, how they got it, and how they live. He specifically calls out the scribes, privileged with social status and an education. He says they “like to walk around in long robes, and to be greeted with respect in the marketplaces, and to have the best seats in the synagogues and places of honor at banquets.”

(Look at long robes. Grimace!)

I mean, who doesn’t like to play dress-up? Hey, I worked hard for that seminary education! And I have to say, when I wear my collar in public, people show me a surprising amount of deference. Three times since I was ordained, someone has anonymously bought me lunch. It’s kinda embarrassing.

Did I earn my role as a priest? Sure, to some degree. But in other ways, it is a function of unearned privilege. What else does Jesus say about the scribes? That despite their showy appearance they actually accomplish a lot of good in the world, so it’s all OK? Let’s check:

“They devour widows’ houses and for the sake of appearance say long prayers. They will receive the greater condemnation.”

Uffda.

Then Jesus pivots to point out a poor widow putting two small copper coins into the temple treasury. They are literally all she had to live on. She has just given it all to God, trusting that God will provide for her in ways that even money could not.

Should we honor what she just did? Should I stand here in my long robes and hold her up as an example? If I did that and stopped there, it would demonstrate clearly that my Master of Divinity has only made me semi-educated. Surely you see that for me to advise anybody to give all their money to the church is to urge people to remain in an endless cycle of poverty!

Yet Jesus appears to hold this woman up as an example of godly living. Right? Isn’t that what we’ve always assumed about this passage? Well, perhaps we’ve always understood this passage wrong. Parse out Jesus’ words a bit. He’s not holding her up as the best example. He’s just observing what happened. She gave all her money to the religious structure, and now she has none.

What will happen to her?

I don’t see Jesus praising this widow’s quiet strength, her unyielding faith, the example she sets for all the rest of us. No, he just points out that there are two ways to look at the math. By raw numbers, she put in the least. But by percentage? She gave 100%, while the rich folks dumping huge piles of money into the box put in … oh, maybe half a percent, but probably far less than that.

Jesus just observes this and moves on. He’s going to let that image bake into the minds of his followers, who will eventually write the gospels so we’ll still talk about it when they’ve died.

Do we fully grasp the systems of privilege and poverty in which we all play a part? It’s all well and good to participate in our democracy and vote for leaders who we believe will move our country in a better direction. But what is that better direction? Do we care enough about the poor widow to listen to her tale? Why did she just give 100% of her money away? What was she thinking? Who will provide for her needs? Do we expect God to see her gift and say, “Well, then,” and radically change her fortunes?

I don’t think God works like that. I think we’re supposed to take care of her. I think that’s always been the case—all the way back to the early church, and then all the way back to the Law of Moses. The ancient Jewish rules for taking care of the poor are quite clear.

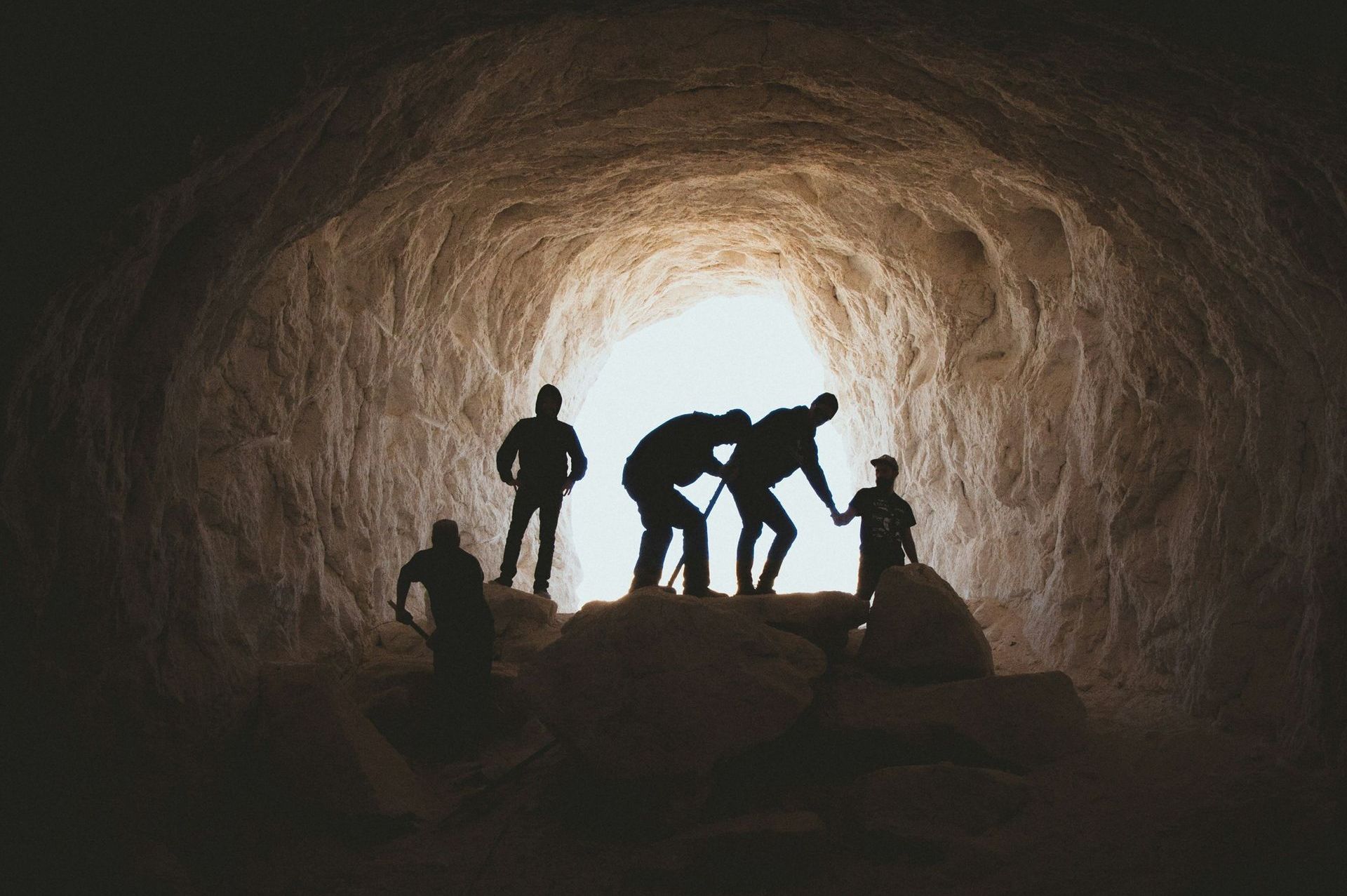

God takes care of people not by helping them win the lottery, but by inspiring us, as individuals and as communities, to carry each other. We are all, at best, semi-educated. We don’t fully understand the larger systems in which we’re always operating. We don’t recognize—or often just choose not to think about—the ways these systems continually exploit the poor.

It is deeply American to assume that the rich have earned every penny, that the poor wouldn’t be nearly as poor if they just worked harder, and that any one of us could become a billionaire with just a little more luck and pluck. Of course, that’s nonsense. Because when the money you have starts making money on its own, you’re no longer earning it. And when you’re working three jobs just to stay afloat, it doesn’t matter how much harder you work. You’re never going to conquer the math of that situation.

Is it even possible to extract ourselves from such systems? If not, what can we do?

When I wrote this sermon, I didn’t know yet how the election would go. I didn’t know whether it would be settled quickly or whether we’d have to resign ourselves to recounts. I didn’t know whether there would be violent troublemakers intimidating voters at the polls. I didn’t know whether there would be riots in the streets. I didn’t know whether all our pre-election anxieties were overblown or spot-on. The only thing I knew for sure was that one of the candidates would declare victory on Election Night even if he knew he’d actually lost. Again.

Well, in our country, voting is our constitutional right, and it’s also our right for our votes to be counted correctly, in keeping with facts and not fantasies. But as Christians, we also carry greater responsibilities.

It is our responsibility not to settle for being semi-educated about what our fellow humans are going through.

It is our responsibility to become ever more aware of the ways our routines and habits take advantage of the vulnerable.

And it is our responsibility to follow Jesus as our ultimate role model, the one who spoke out forcefully against those who choose comfortable ignorance. Jesus boldly set himself up to be opposed by the powerful. According to the Letter to the Hebrews, Jesus’ death was the death not only of an earnest rabbi, but the death of ritual sacrifice, the death of human sin, and the death of hopelessness.

In his death, Jesus became poor like all the rest of us. We will all die, but death is a door that even God has now gone through, and that makes it safe for us. Even in this life, then, death is not a spectre but a part of a pattern for living. When we no longer fear loss, we can free ourselves to participate in God’s political agenda: justice to those who are oppressed, food to those who hunger. Prisoners set free, the eyes of the semi-educated opened. Orphan and widow sustained … the ways of the wicked frustrated.

Friends, the election is over, and our work as citizens and as Christians now continues. Everybody dies just once. What will we do before we die? Will we share our abundance with those who have less? Will we consent to the ongoing education that Jesus offers us?

Look to the psalmist. “Put not your trust in rulers, nor in any child of earth, for there is no help in them. When they breathe their last, they return to earth, and in that day their thoughts perish. Happy are they who have the God of Jacob for their help! whose hope is in the Lord their God.”

Amen.